- Explore Devotee-Driven Supply

- Measures to Maintain Devotee Belief

- Collaboration with National Dairy Boards

- Many Doubts on Private Dairies ‘Cow Ghee’ price

- Establish Dedicated Ghee Production Units

- Setting up On-Site Lab

- Random, Third-Party Audits

- ‘Ghee to Laddu’ Traceability

- Public Display of Test Results

- Reinforce Religious and Ritual Purity

- Placing of Dedicated Personnel

- Geographical Indication (GI) Sourcing

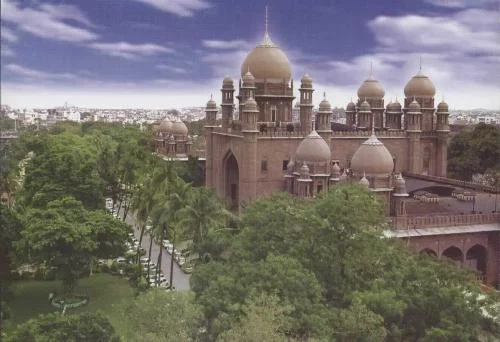

It is time for the governing body of the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD) to implement fair practices in making the ‘laddu prasadam’ of Lord Venkateswara, keeping in view the belief and trust of devotees in the sacred offering. The need of the hour is to prevail and protect the sentiments of the devotees instead of giving scope to political parties, which are making allegations against each other in the name of Lord Venkateswara Swamy for their own political interests. All concerned parties the government, political parties, and spiritual organizations should maintain restraint on the ‘cow ghee and laddu prasadam’ issue first, if they truly have faith in Lord Venkateswara Swamy. The media should stop publishing unverified stories about the ‘cow ghee’ without studying the facts on the ‘pure cow ghee’ availability in India.

The Pure Ghee Reality Check

Firstly, the State government and the TTD Board should study the reality of the availability of ‘pure cow ghee’ in India. They should question themselves first. “Is it possible to buy ‘pure cow ghee’ at the price of Rs. 479 per kilo when the price of it ranges from Rs. 2,500 to Rs. 4,000 per kilo in the open market?” The TTD should constitute an ‘expert committee’ to study the ‘pure cow ghee’ supply and demand in the country, the price at which ‘pure ghee’ can be procured in the open market, and the scope of TTD producing its own ghee by raising cows on its available land.

Secondly, why should TTD make lakhs of laddus using potentially compromised ‘cow ghee’ and offer them to the devotees? The Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD) currently purchases cow ghee at approximately Rs. 470 per kilogram. Other recent tender prices have been aroundRs. 710 per kg. There are also doubts about procuring ‘cow ghee’ at the rate ofRs. 710 per kilo when the market rate of ‘pure cow ghee’ is up to Rs. 4,000 per kilo. In such scenario, the TTD may not get ‘pure cow ghee’ for making sacred laddu.

Thirdly, “There are many questions that need to be answered regarding the supply of cow ghee to the TTD. Specifically, how have private dairies, which do not have their own milk collection centers, been able to supply a massive quantity of ‘cow ghee’ to the TTD at a price ranging from Rs 479 to Rs 710 per kilogram, when the price of ‘pure cow ghee’ in the open market has touched Rs 2,500 to Rs 4,000 per kilogram? The experts from the TTD must study this matter first.”Such a study is necessary after the Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted on the direction of the Supreme Court revealed the ‘cow ghee’ supplied by Bhole Baba Organic Dairy to TTD is not natural cow ghee. How such ghee passed the laboratory tests done by the TTD Lab is the million-dollar question.”

Fourthly, the TTD budget for purchasing ‘pure cow ghee’ at the rate of Rs. 3,000 to Rs. 4,000 per kilo will be high. For this, an expert committee should be constituted to study the ‘pure cow ghee’ issue in detail for the sake of the devotees’ belief. The Dagudu Moothalu (hide and seek) on ‘cow ghee’ must be stopped at any cost. The weight of a Tirupati laddu varies by size: the standard medium laddu weighs about 175 grams and is sold at Rs. 50, the large one is approximately 750 grams for Rs. 200, and the small, free laddu is around 40 grams.

The Scale of Demand

The issue of ensuring pure cow ghee for the massive demand of Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD) laddus is a significant and sensitive matter, particularly in light of recent controversies regarding adulteration. The TTD has a daily consumption of ingredients, including an estimated 13 to 16 tonnes of ghee, for the preparation of over 3.5 lakh laddus. This means that TTD needs approximately 6,000 tonnes, equivalent to sixty lakh kilos, of ‘pure cow ghee’ per year. It is impossible for TTD to buy ‘pure cow ghee’, which is sacred, at the rate of Rs. 479 or Rs. 710 per kilo.

Demand and Dynamics

India faces a growing demand for pure cow ghee, driven by health trends and tradition, with consumption rising to 3.27 per kilo for person (2023-24) from 2.68 kilo (2013-14) and projected to hit 4 kg by 2034. While India produces over 5 million tonnes annually, exact quantitative gaps (shortfall vs. demand) are hard to pin down. However, the demand-supply dynamics show strong growth, with exports exceeding 37,000 MT in 2022-23, indicating robust production. Fodder shortages and quality control remain challenges, suggesting the market is expanding rapidly, but managing intense internal and export demand. India is a top dairy exporter, with over 37,000 MT exported in 2022-23, and sees steady cattle growth. The demand increased due to health consciousness driven by Ayurveda and other health concerns.

Make aware the Devotees on Pure Ghee Gap

The TTD should explain the details of ‘pure cow ghee’ availability to the people and devotees. Challenges included fodder shortages, and deficits in green fodder, dry fodder, and concentrates that impact dairy producers. Ensuring quality and purity of cow ghee amidst high demand presents a significant challenge. Meeting growing institutional (hotels, restaurants) and retail demand requires constant supply chain focus. There isn’t a publicly quantified ‘shortfall’ in metric tons, but rather a dynamic market where rising demand (health, tradition) pushes production and exports, while challenges like fodder supply and maintaining pure quality keep pressure on the system, suggesting strong growth opportunities rather than a critical deficit for quality ghee. The issue of ensuring pure cow ghee for the massive demand of TTD laddus is a significant and sensitive matter, particularly in light of recent controversies regarding adulteration. The TTD has a daily consumption of ingredients, including an estimated 16 tonnes of ghee, for the preparation of over 3.5 lakh laddus.

Ways to Address Ghee Supply with Purity

Given the sacred nature of the offering, the focus must be on sourcing and self-sufficiency rather than compromising on quality. Establishing a dedicated, large-scale cow protection and Ghee production unit is essential. TTD already has cow protection initiatives and this could be significantly scaled up to create a self-sustaining dairy operation, similar to the existing Panchagavya products project, but focused on ghee.

Focus on A2 Ghee Procurement

Focus on procuring pure A2 cow ghee from indigenous breeds, which is highly valued for religious and traditional purposes. This may mean paying a premium price, but it addresses the sanctity of the offering directly. Partner with national and regional dairy development boards like NDDB or state federations, potentially through a long-term, non-bidding contract model to ensure consistent quality over the lowest price. Bypass intermediaries and create direct partnerships with a large network of certified, ethical cow-rearing farmers or dairies across the country. This can secure a stable supply and allow for better tracing of the ghee’s origin. Use the Geographical Indication (GI) tag of the laddu to enforce strict, national-level procurement standards for all ingredients, demanding a high-quality certification like Agmark Special Grade that is rigorously enforced.

Consider the making of laddus of below 50 grams

The TTD should also consider making of laddus below the weight of below 50 grams to reduce the burden of procuring ‘Pure Cow Ghee’. For it, the TTD should make a data from the devotees on the size of laddus, which demand more ‘Pure Cow Ghee’ in the present circumstances. Laddu is believed to be a sacred one and size and weight were nothing. Such thing can be campaigned widely among devotees to reduce the procuring burden of ‘pure cow ghee’ for making laddus. Stop issuing dozens of laddus to a single person. This measure will curtail the pressure on TTD on procuring ‘pure cow ghee first and avert adulteration. Encourage wealthy devotees and philanthropic organizations to sponsor or donate pure cow milk or ghee directly, which can be vetted and used exclusively for the sacred offering. This would connect the devotee’s devotion directly to the prasadam’s purity. As TTD has already begun, establish an exclusive, state-of-the-art laboratory on the premises in collaboration with national food safety authorities like FSSAI or NDDB.

Implement a Fully Transparent and Secure Supply Chain

Use modern supply chain technology (blockchain or QR codes) to track the ghee from the supplier’s plant to the Potu (temple kitchen). This would make it impossible to switch or tamper with the raw material mid-way. Display the quality certification and test results of the procured ghee in a public area or on the TTD’s official website daily or weekly. Transparency rebuilds trust quickly. Continue and emphasize the religious rituals, such as the Shanti Homam and Panchagavya Prokshana, to symbolically cleanse and sanctify the Potu and the ingredients, assuring devotees of the offering’s spiritual purity. Ensure that the personnel involved in the procurement and preparation of the Laddu, especially the Srivaishnavite ‘potu’ workers, are selected, trained, and monitored to maintain the highest levels of religious and hygienic sanctity. By taking these steps, TTD can not only secure a supply of pure cow ghee but also institutionalize a culture of accountability and transparency that will be crucial in preserving the sanctity of the Tirupati Laddu for millions of devotees worldwide.

Editor, Prime Post

Ravindra Seshu Amaravadi, is a senior journalist with 38 years of experience in Telugu, English news papers and electronic media. He worked in Udayam as a sub-editor and reporter. Later, he was associated with Andhra Pradesh Times, Gemini news, Deccan Chronicle, HMTV and The Hans India. Earlier, he was involved in the research work of All India Kisan Sabha on suicides of cotton farmers. In Deccan Chronicle, he exposed the problems of subabul and chilli farmers and malpractices that took place in various government departments.