- Whither Federalism in India?

- (Jab sadak khamosh hai, Sadan aawara banega – R.M. Lohia)

- By Justice B. Sudershan Reddy

- Former Judge, Supreme Court of India

At the very outset let me categorically state that a great honour has been bestowed on me by asking me to speak in the Prof. Rasheeduddin Khan Dialogues. I will assure you that only very few deserve such an honour, and I am way too conscious of my own limitations to ever claim that I deserve it.

I have always maintained that those who come to listen to lectures and participate in discourses, that seek to intensify the working of a constitutional democracy, are the ones to be admired. Especially, in this day and age, when there is a widespread conviction among people capable of reasoned judgement, that even those constitutional values that we thought were non-controversial are under unremitting onslaught.

On the day our Constitution was ratified, Babasaheb had warned that the “temple of democracy, so painstakingly built” by the Constituent Assembly, might be torn down, and that India might again lose its democratic moorings. There is now a justifiable worry whether India is on that slippery slope. So, to all of you in the audience, in as much as you truly represent the hopes and aspirations of “We the people”, especially those who have been historically marginalized and those being freshly marginalized, the real honour belongs to you.

Lamakan has a well-deserved reputation for being a brave open space for freedom to speak on topics that traverse the entire gamut of human knowledge and social & individual action. The only conditions that are imposed, I am told, are that no violence be incited, and the discussions be civil and respectful. Truly an oasis of “deliberative democracy”. To those who have dedicated these wonderful facilities to the cause of free expression and democracy, and who tirelessly organize the activities here – Farhaan, Humera, Elahe, Biju and Azam – I must express my unequivocal appreciation and overwhelming admiration. And also my deepest respect. Thank you for your ceaseless work to keep such a space open.

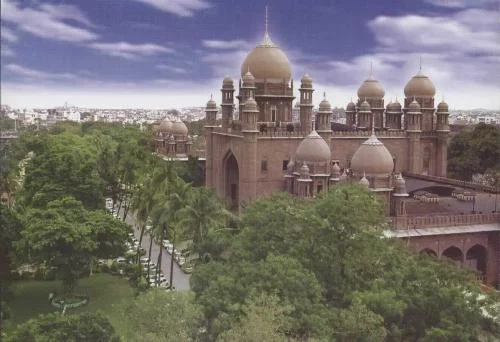

That I am participating in an event associated with Prof. Rasheeduddin Khan is a very emotional occasion for me. Prof. Khan was my teacher when I first came to Hyderabad, to pursue my baccalaureate studies. As a first generation college goer, and hailing from a hardscrabble peasant background from rural Telangana, the prospects – of a University life and the demands of academic rigour in Osmania University – were terrifying. Prof. Khan was of course, one of the intellectual giants who taught in OU at that time. But he was a gentle agnostic giant. A remarkably handsome man, blessed with very kind eyes, and even kinder disposition. Intellectually of course, and economically and socially he was far, far above the station of nearly every student, but he approached his teaching as a joyous task and ever conscious that he was building the capacities of each student for self-actualization. What made him extraordinary were two things. The first was his ability to dissect each concept with analytical precision, exploring the deepest theoretical meanings, and yet retaining an ever insistent concern for its impact on human welfare. The second was his inordinate quest for new information and knowledge – he constantly absorbed information about social life, from the ground, and re-adjusted his perspectives. In that sense he was not merely a political theorist, but also a practitioner. We were truly in awe of him, but he always sought to make us comfortable.

To Dr. Anusha Khan and Kabir Khan

Let me unequivocally state that I owe an immense debt of gratitude to your family. Both for what I learned from your father in the class room, what his life exemplified for us, and of course for initiating these Dialogues in his name. Prof. Khan’s contributions were well known to most of my contemporaries and deeply appreciated by many. His marriage to Smt. Leela Narayan Rao, and their love story, was of course legendary – even if it was spoken about in hushed whispers. For us youngsters it was an indication of how education can enable the breaking of traditional constraints over personal choices. Some twenty odd years after Independence, the inspiring discourses of the founding fathers about still carrying a significant emotional and moral quotient, the love story of a gentle agnostic scholar and an anglicised young Naidu woman indicated a brave new world. (A special word of appreciation for Dr. Anusha Khan for those descriptions that I have borrowed!).

Prof. Rasheeduddin Khan devoted a lifetime to the study of federalism, and federal nation building. He was an exceptional scholar because he had an incredible capacity to distill centuries of debate about federalism, and give shape to application of the principles for the specific context of India. Let us, at this stage, be make it clear to ourselves that federalism, as a topic and field of study, is immensely vast. Even an entire year of lectures would enable us to barely scratch the surface. But I have decided to speak about this topic, all within the span of 45 odd minutes, because the scholarship of Prof. Khan in this area is immensely relevant today. Maybe even more than during the course of his life given the present situation in India.

So, let his words and thoughts, on federalism, ring out today. The following is an extensive quote from the very first page, and the first para of his essay, “Federalism in India: A Quest for a New Identity”

“Among the processes of major transformation of India from a traditional feudal-patriarchal-tribal society to a modern polity while mention is made of industrialization, urbanization, commercialization, democracy, social justice, secularization, political integratio … very rarely” do we talk about “federal nation building. Mostly the term used is ‘nation-building’, which is to be sure quite different from, and one might even add contrary to the process of ‘federal nation-building’. Seen more carefully and profoundly, what is usually referred to as nation-building without the prefix ‘federal’ becomes in a continental polity of India’s spatial size, density of population, and diversities and pluralism of culture and society, an unimaginative authoritarian imposition, an uncritical regimentation, and a negative process of duress to change unity and union of a complex and variegated federal situation into mere uniformity and conformism of a simple unitarian situation.” Let me repeat that last sentence: “… nation-building without the prefix ‘federal’ becomes in the continental polity of ”India“ an unimaginative authoritarian imposition, an uncritical regimentation and a negative process of duress”. And in the same essay, he also writes about the truth:

“that the fundamental unity of India is predicated on its capacity to coalesce its much diversity, in the pattern of autonomy and harmony …. Requires repeated reiteration. In India, unity itself is a federal concept. It is the unity born out of interdependence of diverse socio-cultural entities that passed through” various forms of conflict and reconciliations and “realize that in mutual confrontation they might themselves destroy each other, while in reciprocal co-operation they can thrive, jointly and severally.”

It would probably not be impolite if we were to say that this talk can end here, and that we should all meditate on the content and logic of that brilliant conceptualization. How significantly prescient was his conception of what was then happening and yet to come. Given the tumultuous two thousand years, of formation and demise of many hundreds of polities and kingdoms (obviously also marked by social strife and conflicts), how incredibly historically grounded was his plea for unity in diversity, and reciprocal cooperation. If we needed to quibble, if only because we have lived a couple of decades later and are ever anxious that we might experience even greater horrors, then we might add terms like fascistic undermining of the Constitution, the destruction of progressive agenda for social action that the Constitution seeks to inscribe on our body politic.

Above all, the devaluing of what the Constitution seeks of us – “we the people” – as individuals and also how we interact with each other and protect each other’s rights. A few other concepts we might add, as a precursor to a brief but selective exploration of what Prof. Rasheeduddin Khan’s essay packed, would be of indefeasible “human dignity” in an iterative relationship with fraternity in order to secure the unity and integrity of the nation on the platform of justice, liberty, and equality in the framework of a constitutional democracy marked by a secular, socialist and federal order. And how vesting of uncontrolled power, in one or limited nodes of governance, would be destructive of the possibility of expression of the better qualities of ourselves.

In the past ten odd years we have been witness to the following non exhaustive list of events :

i) Two Presidential Orders abrogated the constitutional autonomy, under Article 370, of the State of Jammu & Kashmir. Subsequently, the Parliament enacted a law converting the State into two Union Territories. Whether one is willing to go into the desirability of consequences of such an action or not, we should, in the least, be concerned about constitutional wisdom about how it was done. The Supreme Court has stamped its approval; but did not engage in any substantive discussion as to how a Presidential Order could amend a Constitutional provision, and bypass the mechanisms for constitutional amendment provided for in Article 368. Let us not forget that Article 368 – which gives the power to amend to the legislature – is not some mere technical or ministerial procedure, but a substantial provision, and a part of the Basic Structure of the Constitution.

ii) After the general elections of 2019, a number of state governments, ruled by opposition parties, were toppled. Defections were “engineered”, parties were split up, and fresh coalitions involving the party in power at the Centre were formed to take over the governments.

iii) A surreal and tragic saga of deliberately obstructing the functioning of a democratically elected government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi for years on end has been writ large on the firmament of centre-state relations. Even though a five judge constitutional bench suggested that such acts were destructive of federalism and democracy. However, the Union government has ignored the wisdom encoded in that judgement. And instead by enacting a law to nullify the limits set by that judgement, has only attempted to usurp power, without paying heed to the constitutional damage that it inflicts.

iv) With regard to the GST regime, many political and constitutional scholars warned that the enactment of [t]he Constitution (One Hundred And First Amendment) Act, 2016 would deprive the states of autonomy as to what will be taxed, by how much and their control over sources of revenue.

Including in instances of natural disasters and the need to raise revenues urgently to meet humanitarian needs of the people.

Though the GST Regime in place today may be technically constitutionally valid, we have to admit its adverse impact on the federal order in India. Simplistic arguments based on “economism” were made to push the Constitutional amendment through, without even providing additional (and autonomous) means of generating revenues for States with particular needs, including when natural disasters can overwhelm their populations.

For instance, in 2018 the State of Kerala asked the GST Council to allow it to levy a cess to generate funds for disaster relief (caused by excessive rainfall and flooding). A Group of Ministers was constituted, a few months later, by the GST Council and it did recommend the allowing of Kerala to levy a one percent cess.This was n a situation that required Government of Kerala to act rapidly. The human suffering of the people due to such delays would have been immense, and the sense of helplessness of the elected Government is damaging to the idea of a federal order. In December of 2024 yet another State was forced to ask the same “concession” to raise funds to help victims of floods. It took the GST Council four months to constitute another GoM to again study the issue. A preliminary search on Google has not revealed whether such a permission has been granted or not. Even if we were to assume that it was, the question still remains: states have been deprived of authority to raise revenue to meet even emergency situations involving grave humanitarian crises.

Given the large share of votes in the GST Council that the Centre has, and each State is puny – in terms of votes – the Centre can arbitrarily and easily deny even legitimate requests. Let us not forget that this is the situation over a revenue source that was originally set aside exclusively for the states to ensure their fiscal autonomy and to enable an independent functioning over the subject matters reserved for the state in the State list and in the Concurrent list. Instead, we frequently witness unedifying spectacle of Chief Ministers of various states lining up to importune Union Ministers and wait for appointments with the Prime Minister. Even in circumstances that involve emergencies and large scale human suffering.

The list can go on and on. But let me round this out with a few more examples.

v) The menace of partisan Governors, playing a not so savoury role in toppling of governments ruled by opposition parties, and refusing to give assent to legislation enacted by duly elected legislatures, and keeping silent on them for many, many months on end, and maybe even much longer. Most of the appointees in recent times, according to informed sources, are long terms members of the party in power in the Centre and the organization that guides it. With regard to the issue of Governors not granting assent to legislation enacted indefinitely, and interminably, not-withstanding the “aid and advice” of the Cabinet, and a Division Bench holding such actions unconstitutional, the situation has become immensely more worrying now. We will discuss this shortly.

vi) Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA) has been repealed and replaced by Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) (VB-G RAM G) Act, 2025. Prior to the introduction of the Bill in the Parliament, little or no notice was given to anyone, the introduction of the bill was not put up to the Business Advisory Committee of the Lok Sabha. The MPs, or at least those sitting on the opposition benches, were not given any time to study the proposed bill and engage in an informed and considered debate. To the best of my knowledge, the proposed bill and its provisions were not shared with the States, nor with the civil society at large.

There is of course justifiable consternation about the fact that Mahatma Gandhi’s name has been removed. However, Mahatma Gandhi – as an idea and an approach to individual and social life – has been systematically killed repeatedly, after his actual physical assassination. A singularly notorious instance was when Savarkar’s portrait was placed directly in front of his in the Parliament. So, maybe it is very late in the day to be talking about being shocked by the removal of Mahatma Gandhi’s name from this or that law, and this building or that.

Apart from the stealthy manner in which the VB-G RAM G was introduced and enacted, a brief and preliminary reading raises serious concerns about federalism. This is a bill sponsored by the Centre and it unilaterally imposes 40 percent of the burden of the scheme on the States; and the States have not been allowed any say in the matter, whether in formal or in informal consultative processes. In contrast, under the MNREGA scheme, almost the entire burden of payment of the wages was to be borne by the Union government. And it was enacted after wide ranging consultations with experts, leaders of the civil society and also with various stakeholders in the states. Consequently, VB-G RAM G appears to be a serious overreach and derogating from the substantive precepts of federalism.It is also a denigration of the stature of the States in constitutional processes. In addition, it contemplates direct interference in how legislative and executive wings of each of the States prioritise how their resources are to be allocated. Moreover, where MGNREGA made the poor of this country rights bearing citizens, and its approach was demand based, the VB-G-RAM-G eviscerates that, reducing the poor citizen to the position of a supplicant.

Secondly, unlike the MGNREGA which set a limited period offive years for it to come into effect all over the country, VB-G-RAM-G Act will come into effect only when the Central Government decides to implement, in only those states or areas of each state where the Central government says it will come into effect, and there is no time limit as to when it will come into effect, if at all, throughout the Country. We should all be extremely worried about this – because it not only enables the Centre to impose a huge financial burden on each state (whose resource raising avenues have been curtailed by the GST regime) in order to avail Central assistance for the poor living in the state to stave off the wolves from their door,

it also gives the ability of the Central Government to discriminate as to which groups of population will receive these benefits. Given that the leaders of the ruling coalition in the Centre are prone to bragging that electing the ruling coalition in the states would ensure the benefits of “double engine” – meaning easier access to greater assistance from the Centre, it would not be unreasonable to conclude that the VB-G-RAM-G Act would give the ruling coalition in the Centre another stick to penalize states ruled by opposition parties. (vii) Let us not forget that the centralization trend does not exist in only one direction, from the states to the Centre. The states also actively oppose decentralization. In this regard, we should reflect upon how 73rd and 74th Amendments – concerning local governance – have been rendered largely ineffective, because the States do not allocate enough funds, do not grant the local bodies adequate sources of revenue, and exercise imperial control.

How should we view the examples briefly described so far. Should we view them as isolated examples of acts by an imperial executive at the Union level and an unquestioning Parliament? Or is there something deeper that is going on? Many scholars have consistently held that there is a strong unitary bias in the very text of the Constitution of India.This was a conscious choice of the Constituent Assembly because there were immense worries of the fissiparous forces that have historically been at play in India. And the members of the Constituent Assembly were obviously aware of the full horror of the violence that is unleashed when those fissiparous forces engulf the society and the polity. So, Constituent Assembly decided to grant more powers to the Centre in order to prevent such forces and the violence that follows. The discussions in the Constituent Assembly clearly indicates that it was not contemplated that the grant of such powers would lead to conclusions that India was largely a unitary state with some federal features. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court took that view for a long time, thereby entrenching the “centralizing tendencies”.

In fact, a significant number of constitutional and political scholars point out that all Constitutions that have sought to inscribe a working democracy on large polities, an impulse of centralization emerges. Amongst the reasons often cited are economic (establishment of a unified market – which to some degree has also occurred in the United States, considered to be a paradigmatic example of a strong federal order as opposed to a unitary form of polity), majoritarian impulses, and when the judiciary interprets constitutional silences to favour the Central governments and/or conflates to ordinary times constitutional powers granted to central governments to handle emergency situations.

In the Indian context, we can clearly discern all three features, though the majoritarian impulse, and systematic othering of the minorities, seems to have emerged in a much stronger form over the past few decades. In the so called socialist phase of economic organization, requirements of planning for the country as a whole meant that the directions were imagined as having to come largely from the Planning Commission and the Central Government. In this phase of liberalization of the economy to instantiate greater play of“market forces”, there also seems to be an instinct to reduce autonomy at the state level, both to instantiate a majoritarian and unitary socio-cultural views based on religion, and also build an oligarchic ordering and control of the economy and the market.

The Courts have not played a consistently salubrious role in protecting the federal structure. In the first instance, Courts adopted an interpretational stance that sought to understand the constitutional power matrix from the perspective of various abstract terminological categorizations. Think of it as attempts to force the matrix described in the Constitution into some kind of theoretical Weberian “ideal types” A bewildering array of expressions have been used: quasi federalism, administrative federalism, amphibian federalism, paramountcy federalism, federal with a unitary bias, coercive federalism, assymetric federalism etc. By undertaking such attempts to pin down the provisions of sharing of power between the Union and the States into some universal typologies, the Supreme Court read a “centralizing tendency” in the Constitution.

An exemplar of this would be the views propounded by the majority in the State of West Bengal v. Union of India . The main tenet enunciated by the majority was that states only exist by the sufferance of the Union, and consequently in the case of any legal conflict between the Union and the States, the Union must always trump. Equally surprisingly, the reasoning of the majority was based on a reading of constitutional (colonial) history, and thought of the Constitution of an independent India as a continuation of constitutional settlements imposed on it by a colonial power. The majority also described the federation structured by the Constitution as not being of a “traditional pattern” – such as the Constitution of United States, and hence thought that should also be a factor in considering the polity inscribed by the Constitution to be more unitary than federal.

The majority also claimed that India has always been a “unitary state” with “devolution of power to provinces being exceptional rather than the norm … The legal conclusion that the Court drew … was that any interpretive dispute between the Union and the States, on question of power, was to be resolved in favour of the Union … This in essence is … centralizing approach to Indian federalism.” But there was a whiff of jurisprudential freshness injected by Justice Subba Rao in his dissenting opinion. After noting the complexity of the social and political situation, he opined: “…our Constitution adopted a federal structure with a strong bias towards the Centre. Under such a structure, while the Centre remains strong to prevent the development of fissiparous tendencies, the states are made practically autonomous in ordinary times, within the spheres allotted to them.”

Justice Subba Rao further continues

“Within their respective spheres, both in legislative and executive fields they (i.e., the Union and states) are supreme….. the emergency powers of the Union to meet extraordinary situations do not affect … exclusive fields of operation in normal times.” It must be noted that Justice Subba Rao’s conclusion is also premised on a reading of history as being marked by repeated conflicts between different regions, parts and interests and hence choice of a “federal order ….” “is to provide against future conflicts.” Gautam Bhatia calls this the “federalizing approach.”

A look at the emergency provisions and the discussions in the Constituent Assembly would clearly demonstrate the correctness of the views expressed by Justice Subba Rao. Article 356 of the Constitution provides that State governments can be dismissed on the ground that the “constitutional machinery had broken down.” When Article 356 was being debated in the Constituent Assembly, members expressed serious reservations that vesting of such a power with the Union could be misused and thereby destroy the federal order. In reply, Babasaheb emphatically said that the purport of the said Article was only to ensure that the Union could act in extraordinary circumstances.

Article 355of the Constitution explicitly casts the burden on the Union to help the state governments govern in a manner consonant with the Constitution. This implied a positive obligation on the Union to not pull the trigger right away, and instead work with the state governments to remove the offending conditions, if any. Babasaheb was emphatic that the provisions of Article 356 were to be used only in the case of extreme conditions, and that too as a last resort. In his words: “these overriding powers do not form the normal feature of the Constitution. Their use and operation are expressly confined to emergencies only … the proper thing we ought to expect is that such Articles will never be called into operation and that they would remain a dead letter.”

It is now well recognized that Article 356 has been grossly misused and abused by the Union from 1950s itself. Sarkaria commission noted that, by early 1990s, it had been used in excess of 90 occasions. While there were some instances of justified use, it was also a fact that in vast majority of instances of use of Article 356 to dismiss state governments was when the party ruling in the Centre was different from the party in the State. This was finally tackled in 1994 by a nine judge bench of the Supreme Court in the S.R. Bommai v. Union of India in which substantive limitations were placed on when the Union could invoke Article 356 to topple a State Government. Most scholars and observers of the centre state relations agree that after the Bommai decision, the number of times that Article 356 has been used has nearly virtually dropped to a paltry few times. This particular decision should be viewed as being equally as important as the decision of the Supreme Court in Keshavanand Bharati case.

Justice B.P. Jeevan Reddy, expanding on what Justice Subba Rao had said, opined : “The fact that under the scheme of our Constitution, greater power is conferred on the Centre vis-a-vis the States does not mean that States are mere appendages of the Centre. Within the sphere allotted to them, States are supreme…. More particularly, the Courts should not adopt an approach, an interpretation, which has the effect of or tends to have the effect of whittling down the powers reserved to the States. Let it be said that federalism in the Indian Constitution is not a matter of administrative convenience, but one of principle – the outcome of our own historical process and recognition of the ground realities.”

The foregoing view (written for himself and Justice Aggarwal, and joined by Justice Pandian) was supported by Justice Sawant (for himself and Justice Kuldip Singh) : “ …. The States have an independent constitutional existence….. they are neither satellites nor agents of the Centre. The fact that during emergency, and of certain other eventualities their powers are overridden … Is not destructive of the essential federal feature of our Constitution … they are exceptions and have to be resorted to only meet the exigencies of the special situations. The exceptions are not the rule.”

The obvious question then would be whether this “federalizing view” is still directing the Courts in their judgements, on questions concerning the power matrix between the Union and the states? Equally importantly, is the Union consistently following the constitutional federal principles enunciated in Bommai? Unfortunately, the answer is no. In the case of NCT of Delhi vs. Union of India , a five judge Constitutional Bench after citingBabasahebs views expressed in the Constituent Assembly, and Justice B.P. Jeevan Reddy’s opinion, unanimously opined (Chief Justice Chandrachud writing for all):

“… it is clear that the Constitution provides States with power to function independently within the area transcribed by the Constitution. The States are a regional entity within the federal model. The States in exercise of their legislative power satisfy the demands of their constituents and the regional aspirations of the people residing in that particular State. In that sense, the principles of federalism and democracy are interlinked and work together in synergy to secure to all citizens justice, liberty, equality and dignity and to promote fraternity among them. The people’s choice of government is linked with the capability of that government to make decisions for their welfare. 74. The principles of democracy and federalism are essential features of our Constitution and form a part of the basic structure. 25 Federalism in a multi-cultural, multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic country like India ensures the representation of diverse interests.

It is a means to reconcile the desire of commonality along with the desire for autonomy and accommodate diverse needs in a pluralistic society. Recognizing regional aspirations strengthens the unity of the country and embodies the spirit of democracy. Thus, in any federal Constitution, at a minimum, there is a dual polity, that is, two sets of government operate: one at the level of the national government and the second at the level of the regional federal units. These dual sets of government, elected by “We the People” in two separate electoral processes, is a dual manifestation of the public will. The priorities of these two sets of governments which manifest in a federal system are not just bound to be different, but are intended to be different.”

Not heeding the constitutional wisdom of the Constitutional Bench, the Union Government immediately moved to nullify the judgement through legislation, within eight days. The same has been challenged in the Supreme Court, and it is pending for nearly two years now. What the Union Government has done is clearly unconstitutional and violates the principles of basic structure, implied limitations and is also manifestly arbitrary. Yet the delays by Supreme Court in deciding the matter reveals another disturbing phenomenon.When the Court is confronted by a recalcitrant Union that keeps throwing up the same issue, again and again, it delaysdelivering judgement. Whether intentional or unintentional, this is tantamount to evasion.

This brings us to the case of the Governor of Tamil Nadu, that was alluded to earlier. The Governor repeatedly did not give his assent to legislation duly enacted by the democratically elected legislature. Complete silence, and the Governor also did not return it to the legislature for reconsideration. Nor were the legislations forwarded to the President, because the specific requirements for forwarding to the President under Article 200 were not met. After many months of repeated “aid and advice” by the cabinet of the State of Tamil Nadu and repeated requests, Tamil Nadu filed a writ in theSupreme Court. Given the precedents, Justice Pardiwala writing for a two judge bench held that such withholding of assent, and not allowing the full operation of the provisions of Article 200 (return for reconsideration) was unconstitutional.

Further, given that this is a recurring problem, the Judge also directed that if Governors do not move under Article 200 and either give assent or return for reconsideration within certain specified and defined time limits then the legislation would be deemed to have come into force, with or without the assent of the Governor. This isa correct view taken by the Supreme Court in State of Tamilnadu v. Governor of Tamil Nadu . It should be noted that the facts were that in respect of some bills, the delays by the Governor was for many years! The writ petition had been filed by the State of Tamil Nadu in 2023, and initially the Court had sought to defuse the situation by ordering the two parties to mutually find a way out of the impasse. The final judgement of the Supreme Court was delivered in April or May of 2025, nearly one and half years later. Remember, this was on top of delays by the Governor for a few years before the State of Tamil Nadu approached the Court. This meant that many duly enacted legislations had been delayed from becoming the law for over three years, in some instances which is more than sixty percent of the life span of an elected legislature.

However, a Presidential Reference was made, seeking an advisory opinion of the Supreme Court on many aspects concerning the decision of the division bench, and some other issues. The Supreme Court decided to accept the reference and rendered a judgement delivered by a five judge Constitutional Bench. The advise given by the Constitutional Bench, in Special Reference No 1 of 2025 , essentially nullifies the ratio of the earlier division bench judgement. Over and above that, it has opened a can of worms that can eat away the foundations of federal structures, bicameralism, and allows un-elected functionaries – who are typically party apparatchiks – to delay indefinitely, the granting of assent of any and all legislations enacted by state legislatures.

And that too not-withstanding the aid and advice of the cabinet of the State.

While technically the advisory opinion does not over turn the judgement of the Division Bench, and is strictly not a precedent under Article 141, in practice it will carry great persuasive value and authoritative weight that other courts and other benches of the Supreme Court are likely to follow.

Can you imagine the mayhem that can be unleashed? As it is, the political discourse of the dominant party, and the mother ship that spawned it and controls it, is that any one holding a different political opinion is “anti-national”. A constituency or an entire state that elects a different party to power is itself deemed to be anti-India, by armies of supporters and even legislators. Under the promises of “double engine growth” lies the darker and a more venal political discourse: that constituencies and states not voting for the dominant party in the Centre (1) will not get the “benefits” of solicitous behaviour of the Central Government that states with the same party in power would get (the discrimination factor) and (2) opposition ruled states might even be “penalised”, and its legislative agenda stifled. There is now the potential of the force of an “unless” command in the hands of the Union executive.

We have seen the demolition of foundational principles of our Constitution

(a) the idea of social justice encoded in the Directive Principles has been almost completely forgotten; and in the economic and cultural discourse, in which oligarchs are the real heroes of the country, (irrespective of the highly suspect practices – of the government and of the oligarchs – that enabled them to amass such wealth and control over such vast swathes of the economy) might it be the case that anyone who talks about economic inequality, and the damage it causes to the well being of the citizens, especially the marginalized, will now be treated as “anti-national”?Maybe call us “urban naxals” and throw us behind bars?

(b) Can we even talk, any longer, about “secularism” as a defining feature of our political and social life? (c) And now, what are we to make of this situation in respect of “federalism” as an essential constitutional feature? How do we even begin to characterize this situation? How did we come to this state of affairs? I turn to my former teacher, Prof. Khan, and I begin to see some light as to what went wrong.

Prof. Khan was clear in his essays that we need to stop enthroning the legal and judicial pronouncements as the last word on what “federalism” entails and that we should get past viewing the elements of “federal order” only as constitutional mechanics. Of course they are that but they are also about pluralism at work in interpersonal relations and inter-group relations in the crucible of social action. And an abiding commitment for pluralism starts with internalization of the ontological belief in the indefeasible dignity of the human as an individual, inheritor of particular set of cultural beliefs and as a part of groups, the vital instantiator of a just social order. The second aspect of this would be the understanding that denigration of dignity of others is necessarily a denigration of dignity of all – irrespective of their faith, socio-economic status, region, linguistic group, caste etc. As Paulo Freire says, we obtain a dehumanized situation when the dignity of some or many is denigrated, or they are exploited. And this is dehumanizing to both the denigrated/exploited and also the denigrator/exploiter. Social transformation, and rebuilding to establish a humanized order would require that both need to be transformed. If we do not have the strength of that belief and the depth of that understanding, then we would also not have the commitment to work to rebuild.

For the past few decades we have been under the onslaught of neo-liberal economic philosophies that essentially tell us that it is morally valid to be selfish, it is ok to ignore the pain of others and not be bothered by what happens to them or the society. Many are also now a part of the global elite that floats on a network of globalised relations, with little or no connections with their own in the country/society. For the individuals who are not a part of that network, as Manuel Castells points out, the socio-economic spheres cause immense angst, and engenders a severe identity crisis. That in turn leads them to identify with more primal groups, in which hatred of others becomes the badge of belonging and basis for socio-political action. Does it sound familiar to our presently lived condition? Equally importantly, this catena of philosophies also misdirect us away from the social, and to the purely selfish realm. Consequently, we remove ourselves from the social, and leave the space to autocrats to take over.

If we do cherish the Constitution and its values – of dignity, of fraternity, of pluralism and of shared present and futures – then the option should be clear – we the people must go back to rebuilding trust in these values amongst the people. There is no other option. Will it be easy? No. Will it mean significant personal costs? Probably it will. I am nearing 80 years of age. I ask myself what can I tell you? What experiences should I share, that I hopemight provide some rudimentary guidance?

Some fifty odd years ago, we the people faced another authoritarian turn. To be sure, the foundations of respect for secular and plural values were still strong. Nevertheless, democracy, and federal structures were under assault. As a young man I was inspired by Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Narayan’s call for total revolution. The time spent amongst the people, I toured different parts of the country, discussing, teaching and learning the values of democracy, and of Constitutional fealty. That was one of my greatest learning experiences. Even as we struggle for the dignity of our fellow humans, the one thing we should remember is that it is also a question of power that is wielded by those we entrust our collective trust. Mark R. Levin warns us that:

“autocrats, of every stripe, and in all ages, have exploited liberty to empower themselves at the expense of liberty of others…..and it” can be a“cancer that apparently metastasizes over time within democracy….. Some 70% of the World’s population currently lives under brutal autocratic regimes… this raises an unpleasant question: Is this the natural state of mankind, at least in the social sense, even if individuals themselves wish for and seek liberty.” This is “negative power, and …. In a democracy negative power typically takes the form of a steadily increasing centralization of authority…… It occurs primarily in three general ways: the imposition by the few (for example the judiciary), the peaceful vote of the many (where people willingly vote for their own demise) or the slow … acquiescence to….. a leviathan. ”

Under our theory of constitutional democracy, the sovereignty finally vests with the people. Gautam Bhatia, a brilliant constitutional scholar, bemoans that after the fiction that people have constituted themselves, the people are then pushed out of the decision making matrix except for a thin layer of authority that is exercised in periodic elections. But there was another guru of mine, who was vital to my understanding of politics and constitutional democracy, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia. He pointed to another way of ensuring that the wielder of collective power is always wary as to what purpose it is being used for. He calls forcontinuous civil disobedience by the people – not in a violent manner, nor merely for undermining the authority of an elected leader, but always within the constraints of constitutional permissibility. The strategy should be to always keep the leader, to who you have entrusted your power, individual and collective, acutely aware of your happiness or disenchantments with how she/he is using the power.

And that is why one of the greatest lessons, for the people who seek to sustain their constitutional democracy, was also very pithily stated by Dr. Lohia:

“Jab sadak khamosh hai, Sadan aawara Banega.”

Jai Hind.

Justice B Sudershan Reddy is a former judge of rhe Supreme Court. He was a judge of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh High Court and Chief Justice of Assam High Court. He is known for his radical judgment in Salwa Judum case. He has been carrying a copy of the Constitution in his pocket for about five decades. He was the candidate of the combined Opposition in the election of Vice President of India recently.