- Dammapet is vital for Telangana’s food security

- Ecological Erosion-

- The Triple Threat to Dammapet’s Farmland

- Sustaining the Seed Bowl-

- Safeguarding Telangana’s Agricultural Future

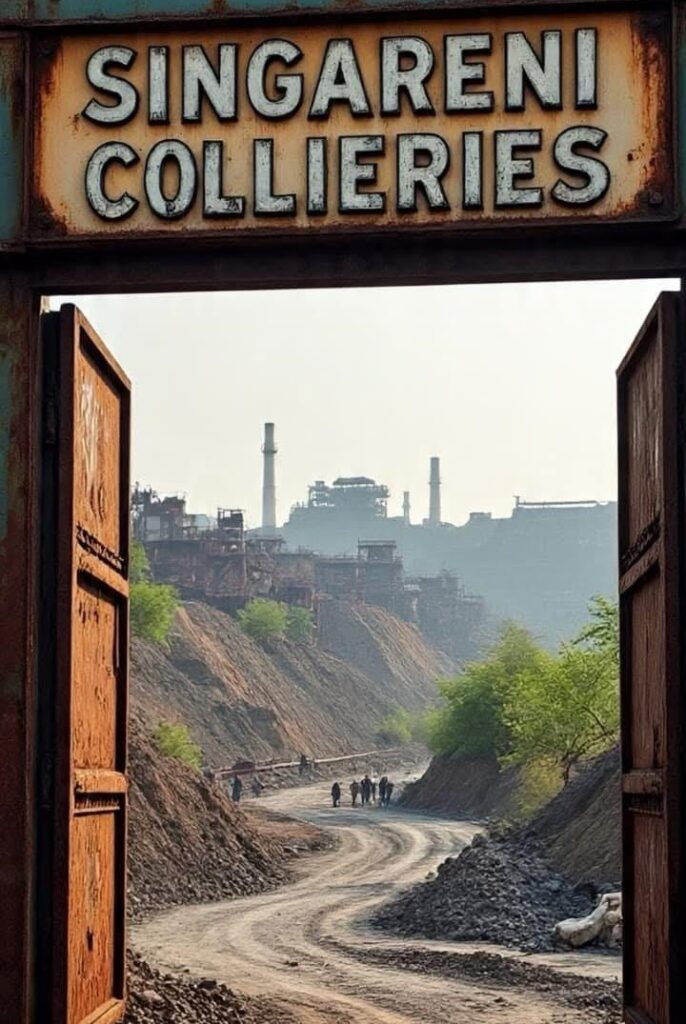

- The Clash of Two Golds

- Industrial Coal vs. Horticultural Prosperity

The relationship between coal and agriculture is a zero-sum game. Without stringent environmental regulations and advanced dust-mitigation technologies, the “black gold” extracted from the earth will continue to cost rural communities their “green gold.”

The Horticultural Powerhouse of Dammapet

Dammapet and its neighbor, Aswaraopet, are renowned for unique agro-climatic conditions that support high-value plantation crops. However, they now face a major environmental threat from the Recharla coal mines on one side and the SCCL mines in Sattupalli on the other. This region is the backbone of Telangana’s oil palm industry, with over 46,000 acres dedicated to its cultivation. Other vital crops include 11,000 acres of mango (producing varieties like Banganpalli and Totapuri), cashew, and cocoa significant plantations that serve as key income sources for tribal and local farmers. The “Mandalapalli-Dammapet” stretch also hosts hundreds of private nurseries, acting as a seed bowl for the entire state.

The Impact of Mining Proximity on High-Value Crops

While coal remains a cornerstone of global energy, its proximity to farmland often spells disaster for local agriculture. The impact of coal mining on surrounding farms is a complex web of soil degradation, water contamination, and physiological damage to crops, creating a cycle of declining yields and economic hardship for farming communities.

According to geological surveys by the AP Mineral Development Corporation (APMDC) and GSI, the Recharla block is one of seven primary blocks in the Chintalapudi belt, with estimated reserves of 14.26 million tonnes of high-grade coal. The estimated availability of quality coal across all seven blocks is 2,000 to 3,000 million tonnes. This quantity is sufficient to produce approximately 8,000 MW of power for 60 years.”

Much of this acreage is currently under high-intensity horticulture. Because these coal blocks are located within three kilometers of the Dammapet border, farmers will experience the impact as soon as overburden operations commence. Interestingly, the Recherla coal mine is just ten kilometers distance to the border of Dammapet mandal.

Soil Degradation and the “Acid Mine” Threat

Surface mining, or open-cast mining, is particularly destructive. It requires the removal of “overburden” the layers of soil and rock above coal seams. This process destroys the natural soil profile, stripping away fertile topsoil and replacing it with sterile mine spoils. Even when land is “reclaimed,” the new soil often lacks the microbial diversity and nutrient density required for high-yield farming.

Furthermore, agriculture relies on clean water, but coal mines often poison local sources through Acid Mine Drainage (AMD). When minerals like pyrite are exposed to air and water, they form sulfuric acid. This toxic runoff leaches into groundwater and streams, lowering the pH to levels comparable to vinegar. When used for irrigation, this water introduces heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, and mercury into the food chain, stunting growth and making crops unsafe for consumption.

Atmospheric Interference: The Silent Suffocator

Even if soil and water remain relatively intact, coal dust carries a persistent threat. Fine particulates settle on the leaves of nearby crops, physically clogging the stomata (pores). This blockage inhibits photosynthesis and reduces the plant’s ability to “breathe” (transpire), leading to thermal stress and significantly lower carbon uptake. Research suggests that dust-covered crops can see a reduction in productivity by several grams of carbon per square meter, effectively “choking” the harvest before it matures.

Socio-Economic Shifts and Future Sustainability

The “Horticulture Web” is more than biological and it is a social network of farmers, laborers, and nursery owners. The influx of mining wealth has shifted some local labor away from farms toward more lucrative (though hazardous) mining jobs. However, environmental degradation threatens the long-term sustainability of this “Green Gold” economy.

The intersection of industrial mining and intensive horticulture in the Sattupalli-Dammapet corridor presents a complex challenge. While SCCL has initiated some reclamation efforts and “Over-Burden” (OB) plantations, more stringent dust suppression and water management strategies are essential. Protecting the horticultural integrity of Dammapet is vital for Telangana’s food security and the preservation of its most productive agricultural landscapes.

Principal Correspondent, Prime Post

Adapa Dora, journalist cum farmer, proved his excellence in both the fields. While working in Andhra Bhoomi (Telugu Paper) and Deccan Chronicle, he forced a famous seed company to pay compensation to the maize farmers for crop loss due to the supply of spurious seeds to them. He wished to maintain harmony between tribals and non-tribals in the mandals of Bhadradri-Kothagudem district for the prosperous of both groups.

Innovative news and information with the future and present position Thanks

బొగ్గు పొడి తో దిగుబడి వస్తుంది అని విన్నాను. దీన్ని ప్రాస్సెస్ చేస్తే ఎక్కువ రిజల్ట్ వస్తుంది అన్నారు. మాకు ఫోన్ no ఇవ్వగలరు