- What next to the Maoist party after the surrender of Mallojula Venugopal Rao along with 60 members?

- Are the present conditions viable for the revolutionaries to come to power through weapons?

- Venugopal Rao and 60 others surrendered to Gachibowli police

- The Road Ahead for India’s Maoists: Ideology, Technology, and Generational Shift

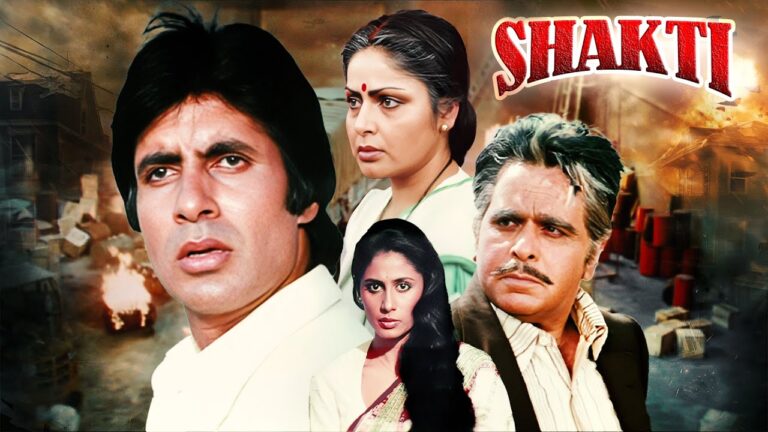

The recent surrender of Mallojula Venugopal Rao, also known by the alias “Sonu,” Politburo member of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), along with 60 other party members and leaders, has cast a sharp spotlight on the viability and future of the Maoist movement in India. The event compels a serious examination of the party’s core strategy, its ability to counter the modern state, and its relevance to the current generation.

The Weapon versus The State: A Losing Battle in the Age of Technology

The foundational Maoist slogan of “coming to power through weapon” faces an existential challenge in the 21st century. The notion of a revolutionary party overcoming the Indian State’s massive military and police apparatus, with its lakhs of modern weapons, seems increasingly untenable.

The Tech Trap

Technical experts and security forces concur that the advent of sophisticated technology has tilted the balance decisively in favor of the State. The use of basic communication tools, like cellphones, by Maoist leaders has reportedly become a “death trap,” leading to the elimination of dozens of top leaders. Furthermore, the State’s access to satellite technology and advanced surveillance capabilities renders traditional guerilla tactics far less effective. The ability of the police to cultivate key party persons for timely intelligence has compounded the losses, neutralizing senior leadership and crippling the organizational structure. In this high-tech security environment, the promise of an armed victory appears to be a statement that may never be fulfilled.

Ideology vs. Aspiration: The Millennial Mindset

While the Maoist ideology’s core tenets equitable resource sharing, care for the poor, and free health and education to all still garner a ‘passive respect’ among some intellectuals and people, the party struggles to connect with the massive young generation.

The Collapse and the Shift

Most of today’s young adults were born after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the general decline of global communism. They grew up in an era defined by globalization, market economies, and technological advancement.

The Goal: This generation’s overwhelming mindset, reportedly encompassing two-thirds of the population, is geared towards becoming ‘rich’ by leveraging advanced technology, professional tools and prevailing liberalizing economic policies.

The Contrast: The austerity and armed struggle advocated by the Maoist party offer a stark contrast to this aspiration. The youth generally do not hold a favorable view of communist parties, making it nearly impossible for the Maoists to secure the support of this “X’, ‘Y’ and “Z” generation’. Even one percent of this generations not aware the names of these leaders.

Historically, communist parties, such as those that came to power between 1917 and 1975 in Russia, China, and elsewhere, did so when the ruling regimes failed to meet the aspirations of a vast majority of the oppressed and when modern technical devices were scarce. Today’s India, despite its inequalities, is a different landscape of aspiration and information.

A Lingering Respect and a Call for Constitutional Change

Despite the strategic failures, many intellectuals and literates maintain a respect for the impeccable characters of Maoist leaders their commitment, dedication, simple life, and capacity for sacrifice. This admiration extends to the Maoists’ core argument against the ‘exploitation of natural resources’ by multi-national companies, which frequently results in the displacement of innocent tribal populations.

However, a section of the society is worried about the continued killing of these dedicated, though misguided, leaders. Their earnest desire is not for the Maoists to become “revolutionary martyrs,” but to work within the framework of the Constitution to achieve their social goals and help the deprived people of the country. The surrender of senior leaders like Mallojula Venugopal Rao, therefore, is not just a police victory; it is a profound signal that the party’s armed path is hitting a technological and generational dead end, prompting a crucial question: Is it time for a radical shift from weapon to word ?

Editor, Prime Post

Ravindra Seshu Amaravadi, is a senior journalist with 38 years of experience in Telugu, English news papers and electronic media. He worked in Udayam as a sub-editor and reporter. Later, he was associated with Andhra Pradesh Times, Gemini news, Deccan Chronicle, HMTV and The Hans India. Earlier, he was involved in the research work of All India Kisan Sabha on suicides of cotton farmers. In Deccan Chronicle, he exposed the problems of subabul and chilli farmers and malpractices that took place in various government departments.